October 06, 2016 | permalink

(Originally published in the October 2016 issue of Inc. magazine.)

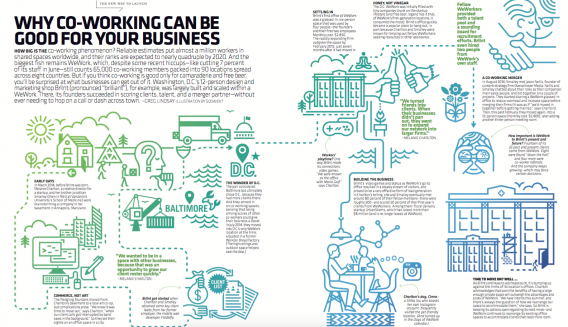

How big is the co-working phenomenon? Reliable estimates put almost a million workers in shared spaces worldwide, and their ranks are expected to nearly quadruple by 2020. And the biggest fish remains WeWork, which, despite some recent hiccups—like cutting 7 percent of its staff in June—still counts 65,000 co-working members packed into 90 locations spread across eight countries.

But if you think co-working is good only for camaraderie and free beer, you’ll be surprised at what businesses can get out of it. Washington, D.C.-based 12-person design and marketing shop Brllnt (pronounced “brilliant”), for example, was largely built and scaled within a WeWork. There, its founders succeeded in scoring clients, talent, and a merger partner—without ever needing to hop on a call or dash across town.

Early days

In March 2014, before Brllnt was born, Melanie Charlton, a creative director for a startup, and her brother Jonathan Smalley, then in R&D at Vanderbilt University’s School of Medicine, were brainstorming a company in her basement in Annapolis, Maryland.

The fledgling founders moved from Charlton’s basement to a local art co-op, but complications arose. “We knew it was time to move out,” says Charlton, “when our client calls got interrupted by band saws in the background.” So they set their sights on an office space in a city.

Brllnt got started when Charlton and Smalley obtained some key client leads from her former employer, the mobile web developer Fiddlefly.

The pair considered Baltimore but ultimately chose D.C. because they had more clients there. And they zeroed in on co-working spaces, sensing that being among scores of other co-workers could give their business a boost. In July 2014, they moved into D.C.‘s only WeWork location at the time, situated in a former Wonder Bread factory. (The high ceilings and outdoor space helped seal the deal.)

Settling in

Brllnt’s first office at WeWork was a glassed-in, six-person space that was used by four people—the founders and their first two employees. Monthly cost: $2,850.

Workers’ playtime? One way Brllnt made its connections: video games. “We were known as the office with Mario Golf,” says Charlton.

Charlton’s dog, Cinna—a Shiba Inu who boasts her own Instagram account—frequently visited the pet-friendly location (and turned up in the “Dogs of WeWork” calendar).

The D.C. WeWork was initially filled with tiny companies drunk on the startup lifestyle (and free beer—legend has it that of WeWork’s first-generation locations, it consumed the most). Brllnt’s office quickly became a popular place to hang out, in part because Charlton and Smalley were known for helping out fellow WeWorkers seeking resources or other assistance.

Fellow WeWorkers provided both a talent pool and a sounding board for recruitment efforts. Brllnt even hired two people from WeWork’s own staff.

Brllnt’s video games and status as WeWork’s go-to office resulted in a steady stream of visitors, and proved to be a very effective form of lead generation. In Charlton’s telling, she and Smalley eventually met around 80 percent of their fellow members—there were roughly 500—and scored 50 percent of their first year’s clients from WeWorkers. Among them: floral delivery startup UrbanStems, which has raised more than $8 million (and is no longer based at WeWork).

A co-working merger

In August 2014, Smalley met Jason Nellis, founder of content strategy firm Overachiever Media. Nellis and Smalley chatted about their roles as their companies’ main salespeople, and bid together on a couple of projects. They started sharing a WeWork glassed-in office to reduce overhead and increase space before merging their businesses (it was as if “we’d moved in together before getting married,” says Charlton). Then, this past February, they moved again, into a 12-person space (monthly cost: $5,400), later adding another three-person meeting room.

How important is WeWork to Brllnt’s present and future? Fourteen of its 33 past and present clients came from WeWork. Eight were found “down the hall,” and four more were co-worker referrals. And the company keeps growing—which may force certain decisions.

Time to move on?

As Brllnt continues to add headcount, it’s bumping up against the limits of its location’s offices. Charlton acknowledges that soon the benefits of having a large enough private space will outweigh the advantages and costs of WeWork. “We have interns this summer, and there’s always the question of how we rearrange our space to accommodate them,” she says. So Brllnt is keeping its options open regarding its next move—and WeWork continues to rearrange its existing office spaces to accommodate clients that need more room.

October 06, 2016 | permalink

(I’m proud to have joined the United States Military Academy’s Network Science Center at West Point as an associated researcher. In theory, that means working with NSC senior fellow Daniel Evans on refining social network models to analyze highly ambiguous environments and predict where precise interventions will make the biggest difference. In practice, it means working with Evans and his crew at Storm King Analytics to help publicize this work and to look for non-military applications. This post is drawn from SKA’s weekly newsletters; earlier installments are further below.)

Before LinkedIn cashed out to Microsoft this summer, CEO Jeff Weiner liked to describe the social network’s culmination as the “economic graph,” a platform encompassing every relationship between the 3.3 billion people employed in the planet’s formal workforce. It’s a classic case of the totalizing logic of Big Data – once we have everything, we’ll know everything – but if LinkedIn users know anything, it’s that the network’s signal-to-noise ratio has proven inversely proportional to its size. The problem with Big Data is that it is simultaneously too big and never big enough.

Using LinkedIn to identify sales prospects illustrates another problem with even the biggest formal datasets – sometimes the person nominally in charge isn’t the one who decides the outcome. One of the foundational concepts in social network analysis is “brokerage” and the related notion of “structural holes.” The University of Chicago’s Ronald Burt was the first to demonstrate how the individuals who manage to bridge these gaps between cliques within organizations produce more ideas, make better decisions, and prosper accordingly – while also being largely invisible. As Burt once told Inc. magazine, a network like LinkedIn “doesn’t answer the question of ‘why them?’ It assumes you know.”

So, what do you do when you don’t know?

This is the question we ask daily at Storm King Analytics, whether it’s in support of our colleagues at West Point’s Network Science Center or on behalf of clients trying to make better sense of opaque environments – who really drives decision-making and how do I influence them to achieve my goals? That’s not a question that can be answered with Big Data; you need something… smarter. Call it “Smart Data,” for lack of a better catchphrase.

A case in point is our work on behalf of a California biotech firm seeking to make inroads in Morocco, which would appear to be fertile territory for companies invested in battling cancer. In recent years, the royal family, led by King Mohammed VI, has led an ambitious campaign to detect and combat cancer early in their subjects. The King’s wife, Royal Highness Princess Lalla Salma, created the Lalla Salma Foundation to marshal public and private partners for help with screening and prevention. But standing in the startup’s way were pharma giants such as Roche, which have operated in the country for more than 50 years. Outmaneuvering them to reach the royals would be difficult, to say the least. So, who was key?

Our approach is to meld qualitative research and cultural expertise with quantitative analysis – half smarts and half data. In this case, we started by mapping the people and institutions commanding power and influence around this particular issue. Broadly speaking, we found four groups with outsized clout:

1. The royal family and their senior advisors. The King of Morocco possesses vast executive powers and keeps counsel with a tight-knit circle of advisors.

2. Société Nationale d’Investissement (SNI). A large private holding company controlled by the royal family. The group has a huge footprint, estimated to be worth 3% of Moroccan GDP.

3. Collège Royale. A secondary school located within the royal palace in Rabat. It specializes in the education of princes and princesses. Selected children of other families may attend, and historically the classmates of royal family members command great status within Morocco.

4. Authenticity and Modernity Party (Parti Authenticité et Modernité-PAM). A political party founded by Fouad Ali El Himma, advisor to King Mohammed VI and the former interior minister. From its founding, it has been a pro-monarchy party with the implicit backing of the King.

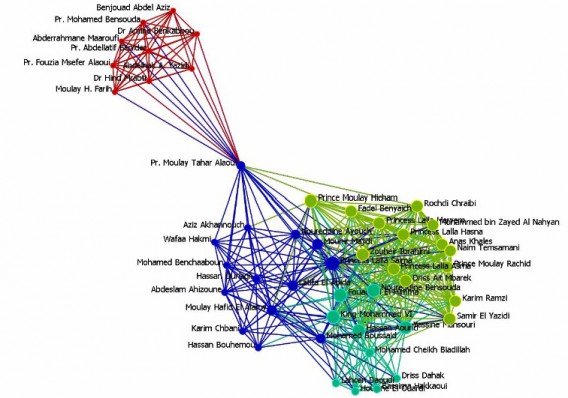

Starting with individuals belonging to these groups, we then added the names of influential members within Morocco’s medical and philanthropic establishment, including Lalla Salma Foundation members and prominent physicians. Populating our model with publicly available biographical details sourced from news outlets, financial databases, Wikipedia, and LinkedIn (why not?), we used these noisy-but-effective portraits to identify connections and create network quantifiably depicting the social capital invested in those relationships.

The result looked like this:

Your eyes don’t deceive you. Our analysis confirms Moulay Tahar Alaoui is far and away the most connected person on this issue in the entire Moroccan establishment.

Wait, who?

Moulay Tahar Alaoui is a prominent doctor practicing at a prominent hospital, the Centre National de Sante Reproductrice – and a royal family insider. He’s not exactly an unknown commodity – he sits on the Lalla Slama Foundation Board and is a member of its Scientific Council – but he wields no decision-making powers of his own. He’s the bridge over the yawning structural hole between Morocco’s medical establishment and its royals. He’s your way in.

Would LinkedIn’s data scientists have arrived at the same conclusion? (After all, we did borrow some of their data.) We don’t think so. Just as Ronald Burt builds his models of organizations through painstaking interviews with stakeholders, our smart data approach combines the qualitative insights of experts with the quantitative muscle of our proprietary to discover connectors like Alaoui hiding in plain sight.

August 30, 2016 | permalink

(I’m proud to have joined the United States Military Academy’s Network Science Center at West Point as an associated researcher. In theory, that means working with NSC senior fellow Daniel Evans on refining social network models to analyze highly ambiguous environments and predict where precise interventions will make the biggest difference. In practice, it means working with Evans and his crew at Storm King Analytics to help publicize this work and to look for non-military applications. This post is drawn from SKA’s weekly newsletters; the first installment is further below.)

Our first few newsletters have focused on what the U.S. Army calls Ungoverned Spaces, which despite the name are neither ungoverned nor spaces – they’re dense, tangled networks of state and non-state actors competing for influence in places where formal governance is weak. In our initial installment, we talked about the four factors driving the emergence of such places: urbanization; globalization; wealthy non-state actors, and technology. Last time out, we visited a place embodying all of these trends – Nigeria’s Emirate of Kano, where a power struggle between four clans to place one of the members on the “stool of power” ended with a surprise succession reminiscent of discarded Game of Thrones subplots.

Why this matters: Ungoverned Spaces like Kano, which sits on the edge of the Sahel along the tenth parallel north, represents the global future of both conflict and commerce. The shadow of Boko Haram stalks the emirate while the city of Kano’s three million residents are only just starting to draw the interest of multinational marketers. To succeed in either endeavor, you need to understand where power truly lies. And to that end, as part of our work supporting the Network Science Center at West Point, we wanted to know whether we could analyze and predict which players would succeed in situations like the succession crisis that consumed the emirate in 2014. So, without further ado…

Dramatis Personae:

• Emir Ado Bayero, successful clan and religious ruler who reigned for 50 years before dying in 2014.

• Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso, governor of the Nigerian state of Kano, who ratifies the selection of the new Emir to square the latter’s status with the state and national power structure. A Muslim, Kwankwaso later ran for president against the Christian incumbent, Goodluck Jonathan, but lost to the eventual winner in his party’s primary.

• Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, the Emir’s grand-nephew who was appointed the Governor of the Nigerian Central Bank in 2009. He was forced to resign in 2014 by Jonathan after alleging corruption in the state’s handling of oil revenues.

• The Sullubawa, Yolawa, Wudilawa, and Dambazawa clans. Each family has its own mosque, royal titles, and representative Kingmaker who helps to elect the next Emir, who is traditionally, but not always, from the Sullubawa clan. (Emir Ado Bayero fit this pattern.)

The Emir’s relationship with Governor Kwankwaso was known to be a tense one. It was also common knowledge that Sanusi harbored ambitions to succeed him. Following Sanusi’ departure from the Central Bank, he returned home and was given a traditional title, “Dan ‘Majen Kano,” reserved for “hardworking and courageous princes.”

Following the Emir’s death, the Kingmakers convened and asked each clan to advance a candidate, one of whom was Sanusi. The Emir’s youngest son (and Sullubawa nominee) Nasiru Ado Bayero was presumed by the press and the public as the front-runner – they were wrong.

Behind the scenes, Kwankwaso was conspiring with Sanusi to retaliate against the Bayero family for their warm relations with President Jonathan while strengthening his position for a presidential run. When Sanusi’s selection as the new Emir was announced in June 2014 just two days after Bayero’s death, crowds gathered to protest what they intuitively grasped was a rather… opaque decision-making process. Once it became clear Sanusi would get the nod, his rivals allegedly plotted to kidnap him – a scheme reportedly foiled at the last minute by Kwankwaso’s protection.

Their plan worked. Nasiru Ado Bayero left Kano shortly thereafter, refusing to acknowledge Sanusi’s legitimacy. But that didn’t matter, because he was stripped of his post and family title following Jonathan’s defeat by President Muhammadu Buhari in 2015. (Kwankwaso lost to Buhari, but later ran for Senate and won.)

That’s the end of our story. But this rather tidy resolution raises a number of questions for a military commander on the ground charged with hunting Boko Haram, foreign companies seeking to do business in a city they can barely navigate, or an investor wondering where power lies: how could we have known Sanusi was secretly the front-runner? Was Kwankwaso destined to outmaneuver the Bayeros and the Sullubawa clan? And was the root of their animus purely the result of religion and presidential politics, or were there other factors at play?

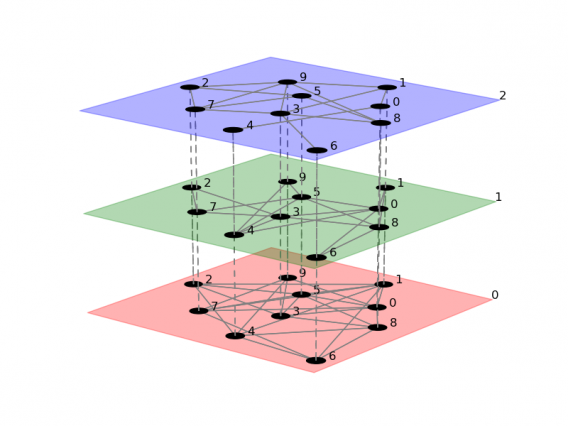

That’s where we come in. We build tools that quantify social capital – a currency measured in connections, reciprocity, and trust – and use them to create multi-layer network models that describe and visualize competing and cooperative actors in a social network like Kano’s. Using statistical tools like Network Kernel Density estimations, we can take these models, compare them to others, and map how they function. The last step – and this is where things truly get interesting – is to choose a goal (do you want to see Sanusi on the stool or power, or Bayero), and use our proprietary algorithms to determine how best to nudge the network toward your desired outcome. In Kano’s case, that means plotting the half-dozen steps necessary to get cozy with Kwankwaso and tip the scales in Sanusi’s favor.

An example Multi-layer Network

An example Multi-layer Network

None of this foolproof, of course – unlike chess pieces, people have a mind of their own. Which is why we’ve added the ability to forecast the consequences of our recommendations while taking into account networks that are constantly evolving. Speaking of which, we’re currently mapping the most influential actors in the Horn of Africa and the tribes of the Maghreb for the U.S. government. Using these additional network datasets, we’ll continue to refine our methodology and algorithms.

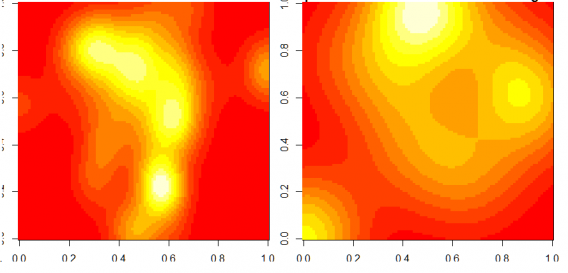

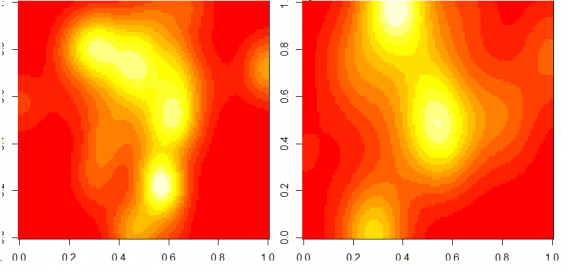

Comparing 2 networks using Network Kernel Density. The “goal network” is on the left.

Comparing 2 networks using Network Kernel Density. The “goal network” is on the left.

After running our algorithm for 10 steps the network on the right more closely resembles the “goal network.”

After running our algorithm for 10 steps the network on the right more closely resembles the “goal network.”

Our ultimate goal is to develop an analytical engine that automates this process for decision makers for both military and commercial purposes. As you might imagine, the uses of a such a tool go far beyond military applications – knowing who to befriend is as much if not more valuable than knowing who to fight.

August 30, 2016 | permalink

(I’m proud to announce that I’ve been appointed to the United States Military Academy’s Network Science Center at West Point as an associated researcher. In theory, that means working with NSC senior fellow Daniel Evans on refining social network models to analyze highly ambiguous environments and predict where precise interventions will make the biggest difference. In practice, it means working with Evans and his crew at Storm King Analytics to help publicize this work and to look for non-military applications. The first installment of SKA’s newsletter is below.)

In Silicon Valley, it’s not uncommon for self-described disrupters to self-consciously slip the acronym “VUCA” into conversation. VUCA, which stands for “volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity,” describes the rapidly shifting landscape on which future competition and conflicts will take place. But it wasn’t coined by product managers at Facebook to describe cutthroat competition in the mobile ad space. VUCA was invented by the U.S. Army War College to instill in commanders that traditional war-fighting doctrine, functions, and hierarchies no longer necessarily apply.

While amateurs talk of disrupting established competitors, the professionals in the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) are wondering what it’s like to fight in places where there’s no establishment at all. In Pamphlet 525-8-5, TRADOC predicts:

Future operational environments will be characterized by uncertainty, complexity, rapid change, and a range of potential threats. They will be marked by various levels of conflict among nations and groups competing for wealth, resources, political authority, sovereignty, and legitimacy. The distinctions between threats will blur for the U.S. These include, for example, the nature of enemies and adversaries, and the multiplicity of actors involved. In addition, friendly and unfriendly actors will attempt to adapt to an ever-changing environment, which may lack a system of governance or rule of law.

The most challenging of these environments, where VUCA rules, are known as Ungoverned Spaces. These are the places where national sovereignty effectively stops – whether on remote mountaintops, in slums, in labyrinthine offshore accounts, or even in cyberspace. Whether emerging from the ruins of a failed state or the hollowing out of national power from within, the world is now littered with Ungoverned Spaces like the terrorist havens of Waziristan and Yemen, the empty quarters of the Sahel and Maghreb, megacities as varied as Rio de Janeiro, Karachi, and Lagos, and most famously the territory controlled by Islamic State.

Ungoverned Spaces aren’t voids but the opposite – places where dense, overlapping networks of local actors compete for legitimacy in the absence of a strong state, NGOs, or multinational corporations. Picture São Paulo drug gangs providing favela residents protection, or Islamic State’s efforts to win hearts and minds by employing “warfare through welfare.” These are places where the rule of law and formal governance is suspended, replaced by a combustible mixture of threats and promises administered through personal relationships opaque to outsiders. Every Ungoverned Space is ungoverned in its own way. But simply knowing that doesn’t help you much.

Which is why our team here at Storm King Analytics have been supporting an Army Studies Program study of Ungoverned Spaces in support of the Network Science Center at West Point. As its name implies, our goal was to develop a multi-layer model capable of analyzing the actors and relationships embedded within and across these competing networks, and once we had done that, identify and assess opportunities for interventions.

In other words, rather than charging into environment we don’t understand, could we subtly tweak the networks to produce more desirable outcomes from a military perspective?

To test this hypothesis, we had to do three things: understand what’s driving the metastasis of Ungoverned Spaces; select one such space for analysis, and make predictions that could be proven over time. For now, let’s stick to why.

Ungoverned spaces are driven by four factors: urbanization; globalization; the rise of non-state actors, and the technology enabling them.

The planet’s urban population is set to double in the first half of this century to more than 7 billion, while urban land cover is poised to triple. The vast majority of this growth will be concentrated in slums and other informal settlements – classic Ungoverned Spaces where services are locally provisioned.

The second trend, globalization – especially migration and infrastructure networks – feeds the first, leading to transnational migrant communities whose inner workings are illegible to their host countries (as seen in the Paris and Brussels attacks plotted from the relative obscurity of the immigrant neighborhood of Molenbeek in Brussels).

Perhaps most alarming is the mounting wealth of non-state actors. Whether it’s Mexico’s Sinaloa drug cartel or Islamic State (and its oil revenue), their multi-billion dollar cash flows increase the opportunities for state capture through a combination of fear and bribery, or even the replacement of state services altogether. It also potentially expands their reach from local or regional actors into global ones through offshore money laundering and investments.

That’s driven by the fourth factor, technology, which has consistently made the ability to connect, coordinate, and execute hostile activities more easily, efficiently, and invisibly. Three days before last fall’s Paris attacks, for example, the Belgian federal interior minister acknowledged Islamic State’s preference for using the Sony Playstation 4 network for communication. It turned out they didn’t even need encryption.

Ironically, these are more or less the same factors that have emerging markets investors salivating. For instance, in their book No Ordinary Disruption: The Four Global Forces Breaking All the Trends, the directors of the McKinsey Global Institute name three of the same four, only electing for aging demographies over non-state actors. Meanwhile, private equity investors like the Dubai-based Abraaj Group have built multi-billion-dollar portfolios in the same markets focused on companies using technology to serve urban customers.

Given the scale and scope of the forces at work, perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that one army’s threat is private equity’s next fund-raising opportunity. In the next installment of this newsletter, we’ll introduce you to a place that ticks all the boxes on McKinsey’s checklist and could double as a plot line on Game of Thrones. As it turns out, these things are not unrelated. (Skip ahead if you’re dying to know who plays the Lannisters and the High Sparrow.)

We introduced Ungoverned Spaces and these factors in more depth in a recently published paper. Next time, we’ll visit the site we chose: the Emirate of Kano.

July 30, 2016 | permalink

I’ve spent much of the last two years speaking about the future of mobility at the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile, Transport for London, UITP, the kickoff event for Dubai’s Expo 2020, the MIT Media Lab’s Disrupting Mobility conference, the American Automotive Leasing Association, the Automotive Fleet Leasing Association, the French Automobile Club Association, the California Transit Association, and many, many other associations.

But I’ve never had video of those talks before now. Yet another group – Trapeze Group N.A., which supplies software to transit agencies – kindly invited me to deliver the opening keynote of their User Conference in San Antonio this past April, and the video has just been posted online. To watch, please click here (or the image above) to be taken to Trapeze’s site, where you will be required to register. (The video is free.) It’s worth it, I promise. Fast-forward to the 9:00 mark for the start of my talk.

July 29, 2016 | permalink

On July 20, I was invited by the The Guardian to join a Web livechat (they still do those!) answering the question, “How will you commute in 2030?” As you can imagine, I had a lot to say on the subject. Here are a few highlights.

Asked to describe the future of transport in a paragraph, I couldn’t avoid the question of cars:

Globally speaking, I think the biggest change will be: more cars. A LOT more. I’m not excited by this prospect – in fact, I feel the opposite – but having recently studied trends in cities like São Paulo and Manila, the combination of rising middle class incomes and the separate of jobs and housing are driving unprecedented rates of auto ownership. New car sales in Manila nearly doubled between 2013-2015. Nairobi has seen the number of cars on the road double every six years, and so on. (And then there’s the autonomous car hype.) So, that’s the challenge.

But the real driver of change is the two-way communication and coordination capabilities of the smartphone:

“Cities are always created around whatever the state-of-the-art transportation device is at the time,” Joel Garreau wrote twenty-five years ago in his book EDGE CITY. Back then, it was the cutting edge combination of cars and PCs that spawned the suburban edge cities of Garreau’s title. Today, the state-of-the-art in transportation is the smartphone, meaning the ability to discover and coordinate modes is more powerful than any single mode on its own, as reflected in Uber’s $68 billion market cap. How will cities and transport agencies like TfL respond?

On the role of public transport in this brave new world:

Public transport is more critical than it’s ever been, and perhaps more in danger. It’s taken thirty years to evolve from the judgment famously (though falsely) attributed to Thatcher that, “a man who, beyond the age of 26, finds himself on a bus can count himself as a failure ,” toward Bogota Mayor Enrique Penalosa’s assertion that “an advanced city is not one where even the poor use cars, but rather one where even the rich use public transport.” My biggest fear is that autonomous cars (which will happen because the the tech is maturing and the social mandate to save lives lost in traffic collisions will demand it) and private mobility services will fatally undermine public transport in favor of private mobility services. Public transport operators need to think of themselves as the managers of cities’ total mobility systems, rather than the people who make the trains run on time. (Although that’s still important!)

Sheer physics means cities like London will always need excellent train and bus service – there’s simply no way to replicate their capacity. That’s also true for Tokyo, New York, and a few hundred cities with the density and land-use that works hand-in-hand with public transport.

What can public transport learn from Uber?

People want more reliable, frequent service. Period. You can keep your WiFi-equipped buses.

But I agree with Chris that reducing uncertainty and anxiety should be a primary goal. Maybe Uber’s greatest innovation wasn’t making it possible to summon a car with your phone, but being able to watch the car drive to your location – people find that proposition overwhelmingly appealing. People would be more inclined to use public transport if you could reassure them ahead of time that the system will get them where they want to go on time.

Also, the great selling point of “mobility-as-a-service” or other multi-modal subscription schemes could be the availability of cars in the network. I think people would also be inclined to rely more heavily on public transport if they know there’s a car for them when they need it. It’s a security blanket for commuters.

And what can we learn from informal transit, which is the dominant means of commuting across much of the world?

Elsewhere, I’m intrigued by what we can learn from informal transport, i.e. the 14-20 seat minibuses seen in Manila (jeepneys), Nairobi (matatus), Mexico City (pesero), Mumbai (auto-rickshaws), Bangkok (songthaew) and so on. What would happen if those were networked together?

The question was asked: why don’t we simply commute to someplace closer to home?

A complicated question! While there are certainly opportunities to reduce commutes through coworking and cloud commuting, the fact remains that London and other cities are what they are because of their ability to compress dense social networks of people together in space and time to share ideas. All of our lovely ideas about innovation spring from that.

That said, I think the notion of commuting daily to the same office (which only achieves a 40% peak utilization rate) is rather outdated. It will be interesting if neighborhood work hubs catch on (right now, they’re called coffee shops), and I know that in Manila, Regus wants to open hundreds of new locations so that when the freeway traffic becomes unbearable, you can exit and work from the near branch.

Finally, the moderator asked for the ideal solution for commuting:

The best way to commute remains walking. And I’m cheered a bit by the fact that here in America, there is a growing preference (as seen in rents and housing prices) toward infilling auto-dependent suburbs with more walkable, mixed-use environments. The only way to create a more humane commute over the long run is through significant changes in land uses, and that may take a while.

You can read the entire chat here.

July 29, 2016 | permalink

I have a pair of mentions in The Washington Post and Christian Science Monitor this morning respectively praising trains and warning about “smart homes.”

The Washington Post’s Dom Philips wonders whether next month’s Summer Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro will be a traffic apocalypse despite last-ditch efforts to open new metro and bus rapid transit lines in time. BRT is a good start, I said, but ultimately insufficient:

Greg Lindsay, a visiting scholar at New York University’s Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management, said that setting up a bus rapid-transit system is less expensive and faster than building metro lines. But the buses carry fewer people – 17,000 an hour compared with 80,000 or more an hour for a metro line.

“The costs are cheaper at the beginning, but maintenance costs over time are higher than rail,” he said. “You need to take BRT routes and eventually turn them into rail.”

Meanwhile, the Christian Science Monitor asks if Amazon’s voice-activated digital assistant, Alexa, is only the beginning of what will become increasing smart homes. The piece mentions the report I co-wrote and presented in March with the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative on the perils and unintended consequences of such tech:

Panelists at an Atlantic Council event March 31 suggested the lack of guidelines for internet-connected devices in the home could even be used against consumers, as the Monitor’s Jack Detsch reported.

“In the future, if you’re behind [on payments], you could be locked in your house until you pay back your bills,” Greg Lindsay, a senior fellow at the New Cities Foundation, told the Monitor.

We live in interesting times.

July 21, 2016 | permalink

Last month in Montreal, I attended my fourth(!) New Cities Summit. This time around, I was asked to host the second day’s opening panel on “mobility as a service,” i.e. what happens when we tie car-sharing, bike-sharing, ride-hailing and public transit together into a single service. I was joined onstage by: Timothy Papandreou, ‎director of the office of innovation at the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (who has since left for Google); Nicola McLeod, Zipcar’s GM for Canada; Luc Sabbatini, CEO of PBSC Urban Solutions (owners of the Bixi bike-sharing program), and Andrew Salzberg, global mobility policy lead for Uber.

Click the video above and watch as I grill each panelist in turn about whether they would ever play nice with a city-run mobility-as-a-service scheme. (Reading between-the-lines consensus: probably not.)

July 21, 2016 | permalink

(This week, Daimler demonstrated its first autonomous bus in Amsterdam, followed on Wednesday by Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk’s promise to reinvent the bus altogether: “With the advent of autonomy, it will probably make sense to shrink the size of buses and transition the role of bus driver to that of fleet manager. Traffic congestion would improve due to increased passenger areal density by eliminating the center aisle and putting seats where there are currently entryways, and matching acceleration and braking to other vehicles, thus avoiding the inertial impedance to smooth traffic flow of traditional heavy buses. It would also take people all the way to their destination. Fixed summon buttons at existing bus stops would serve those who don’t have a phone. Design accommodates wheelchairs, strollers and bikes.”

In their honor, I’m republishing an essay originally published on Quartz in Nov. 2014 with Anthony Townsend in which we called for autonomous buses to take priority over autonomous cars.)

The self-driving car has traveled a long and lonely road to get here. Introduced to the American public by General Motors at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, the Depression-era dream of automated highways has perpetually lagged behind the present in drivers’ rear-view mirrors. But thanks largely to Google, the future once again appears to be gaining on us. A panel of Silicon Valley technology leaders recently polled by The Atlantic expects the first fully autonomous models to roll into our driveways in 2022.

But don’t count on it. The autonomous car will not be nearly as autonomous as its champions would have you believe.

When Google’s car took its first official driving test in Nevada in 2012, it struggled at times to pass–and this was on a course and under conditions of the company’s choosing. According to the state examiner’s log published last month by IEEE Spectrum, the self-driving Toyota Prius needed human help making turns and surrendered control completely when faced with the ambiguous terrain of roadside construction. The car wasn’t tested at all at railroad crossings or roundabouts, and Nevada’s DMV had agreed beforehand not to drive it in snow, ice or fog–none of which the car was designed to operate in.

Of course, self-driving cars will get smarter as computing power increases. But they will quickly encounter another real-world complication: other breeds of self-driving cars. In September, California joined Nevada in granting autonomous licenses, and within hours Audi and Mercedes-Benz squeezed ahead of Google in securing permits. There were merely the first in line. General Motors’ Cadillac division announced in August it would offer limited autonomy by 2017, and Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk recently unveiled the Model D, an electric sedan with its own semi-autonomous features.

Further complicating matters will be unpredictable human drivers, who won’t give up their cars en masse. A survey of 1,533 US, UK, and Australian drivers published by University of Michigan researchers in July found that a majority of respondents had serious concerns about riding in autonomous cars–and more to the point, they wouldn’t pay extra for them. It’s taken more than a decade for drivers to seriously consider switching to hybrid and electric vehicles; it will take decades more to achieve a majority of self-driving vehicles on the roads.

As a result, by the time Google’s cars are ready for sale, they will have to share the roads with a slew of models produced by dozens of automakers, each with its own scheme for avoiding collisions. With traditional rules of the road shoved aside by overly cautious computers, one result might be epic gridlock, as they slow to a crawl attempting to work it out. Meanwhile, all the focus on vehicular autonomy has overshadowed the slow progress on essential protocols for car-to-car communications, an essential technology for mass automation of our roads. Drivers can expect years of technical and legal wrangling in addition to incompatibilities and glitches as Google’s and Tesla’s cars try to talk while traveling 60 miles (96 km) per hour. Tough security problems abound and various proposals to shuffle the unique ID of your car–so that it doesn’t become a privacy-compromised tracking device like your phone–have yet to be worked out.

Google knows this game well. The 20-year history of the commercial internet has been marked by brawls between corporate giants over which program or protocol should be the industry standard. Microsoft won the Web’s “browser wars” of the 1990s and ultimately lost an antitrust case because of it.

That said, Google’s greatest shortcoming isn’t its technology, but how it has defined America’s transportation challenge. Our public transportation systems are running near historic highs in ridership, while using technology and business models from the 19th century. We should be upgrading these, not trying to fix America’s auto-dependent suburbs.

Consider buses. These are experiencing a renaissance as cities around the world, from Bogota to Guangzhou to Jakarta, have shown how bus rapid transit can be a faster, cheaper, more flexible and energy efficient way to move large numbers of commuters than either cars or trains. Now what if those buses–like the private automobile “platoons” envisioned by the auto industry–could travel safely only feet apart at top speeds?

This scheme could solve some of the most challenging transportation problems facing American cities. With its rail tunnels in desperate need of repair after Superstorm Sandy in 2012, the New York region needs alternative ways of moving commuters across its rivers. According to a recent estimate (pdf, p. 11) by Jerome Lutin, New Jersey Transit’s former director of planning, and Alain Kornhauser, the head of Princeton University’s transportation program, if self-driving buses could maintain a safe separation of just six feet (1.8 m)–well within near-term technological capabilities–the bus lanes of the Lincoln Tunnel, connecting New York City to New Jersey, could accommodate over 200,000 passengers per hour, more than five times today’s throughput.

Google’s engineers may have resurrected the dream of fluid mobility, but they have a lackluster vision of how to implement it. Before we chase the ghosts of yesterday’s tomorrows, we need to think harder about how self-driving vehicles will actually perform in the real world, and more important, how they can be used not just to repair but to reinvent our transportation systems.

July 15, 2016 | permalink

Last month, I joined architects James Sanders and Scott Francisco, along with Cubed author and N+1 senior editor Nikil Saval, to discuss the future of work and workspaces as part of the Durst Conference 2016 – the annual event hosted by Columbia University’s Center for Urban Real Estate (CURE). Sanders kicked off the discussion by asking each of us to unpack a word. Nikil’s was “efficiency;” Scott received “technology,” and mine was “innovation” – a subject on which I had no end of commentary.

Video from the entire conference is posted above; Sanders’ opening remarks for our session begin at the 7:40 mark, the panel begins at 24:00, and I appear at 47:00.

» Folllow me on Twitter.

» Email me.

» See upcoming events.

Greg Lindsay is a generalist, urbanist, futurist, and speaker. He is a non-resident senior fellow of the Arizona State University Threatcasting Lab, a non-resident senior fellow of MIT’s Future Urban Collectives Lab, and a non-resident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Strategy Initiative. He was the founding chief communications officer of Climate Alpha and remains a senior advisor. Previously, he was an urban tech fellow at Cornell Tech’s Jacobs Institute, where he explored the implications of AI and augmented reality at urban scale.

----- | January 22, 2024

The Future of Generative AI in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction

----- | January 1, 2024

----- | August 3, 2023

CityLab | June 12, 2023

Augmented Reality Is Coming for Cities

CityLab | April 25, 2023

The Line Is Blurring Between Remote Workers and Tourists

CityLab | December 7, 2021

The Dark Side of 15-Minute Grocery Delivery

Fast Company | June 2021

Why the Great Lakes need to be the center of our climate strategy

Fast Company | March 2020

How to design a smart city that’s built on empowerment–not corporate surveillance

URBAN-X | December 2019

CityLab | December 10, 2018

The State of Play: Connected Mobility in San Francisco, Boston, and Detroit

Harvard Business Review | September 24, 2018

Why Companies Are Creating Their Own Coworking Spaces

CityLab | July 2018

The State of Play: Connected Mobility + U.S. Cities

Medium | May 1, 2017

Fast Company | January 19, 2017

The Collaboration Software That’s Rejuvenating The Young Global Leaders Of Davos

The Guardian | January 13, 2017

What If Uber Kills Public Transport Instead of Cars

Backchannel | January 4, 2017

The Office of the Future Is… an Office

New Cities Foundation | October 2016

Now Arriving: A Connected Mobility Roadmap for Public Transport

Inc. | October 2016

Why Every Business Should Start in a Co-Working Space

Popular Mechanics | May 11, 2016

Can the World’s Worst Traffic Problem Be Solved?

The New Republic | January/February 2016

January 31, 2024

Unfrozen: Domo Arigatou, “Mike 2.0”

January 22, 2024

The Future of Generative AI in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction

January 18, 2024

The Promise and Perils of the Augmented City

January 13, 2024