November 12, 2014 | permalink

Innovation doesn’t happen at your desk from amandabaillieu on Vimeo.

On November 11, Amanda Baillieu and NBBJ London were kind enough to host me for Archiboo, a series of talks about the future of architecture and urbanism. I spoke about – what else? – engineering serendipity and the necessity of designing new organizations, environments, and networks capable of generating new connections between people and ideas. Amanda was kind enough to tape the entire talk – please watch.

November 03, 2014 | permalink

(Medium has partnered with The Aspen Institute to publish essays based on talks at this year’s Aspen Ideas Festival. What follows below was based on my talk titled “Engineering Serendipity,” and was originally published on October 30, 2014.)

I’d like to tell the story of a paradox: How do we bring the right people to the right place at the right time to discover something new, when we don’t know who or where or when that is, let alone what it is we’re looking for? This is the paradox of innovation: If so many discoveries – from penicillin to plastics – are the product of serendipity, why do we insist breakthroughs can somehow be planned? Why not embrace serendipity instead? Because here’s an example of what happens when you don’t.

When GlaxoSmithKline finished clinical trials in May of what it had hoped would be a breakthrough in treating heart disease, it found the drug stank – literally. In theory, darapladib was a wonder of genomic medicine, suppressing an enzyme responsible for cholesterol-clogged arteries, thus preventing heart attacks and strokes. But in practice it was a failure, producing odors so pungent that disgusted patients stopped taking it.

Glaxo hadn’t quite bet the company on darapladib, but it did pay nearly $3 billion to buy its partner in developing the drug, Human Genome Sciences. The latter’s founder, William Haseltine, once promised a revolution in drug discovery: After we had mapped every disease to every gene, we could engineer serendipity out of the equation. Darapladib was to have been the proof – the product of scientists carefully picking their way through the company’s vast genetic databases. Instead it’s a multi-billion-dollar write-off.

Big Pharma is hardly alone when it comes to overstating its ability to innovate, although it may be in the worst shape. By one estimate, the rate of new drugs developed per dollar spent by the industry has fallen by roughly a factor of 100 over the last 60 years. Patent statistics tell a similar story across industry after industry, from chemistry to metalworking to clean energy, in which top-down innovation has only grown more expensive and less efficient over time. According to a paper by Deborah Strumsky, José Lobo, and Joseph Tainter, the average size of research teams bloated by 48 percent between 1974 and 2005, while the number of patents per inventor fell 22 percent during that time. Instead of speeding up the pace of discovery, large hierarchical organizations are slowing down – a stagflationary principle known as “Eroom’s Law,” which is “Moore’s Law” spelled backwards. (Moore’s Law roughly states that computing power doubles every two years, a principle enshrined at the heart of technological progress.)

While Big Pharma’s American scientists were flailing, their counterparts at Paris Jussieu – the largest medical research complex in France – were doing some of their best work. The difference was asbestos. Between 1997 and 2012, Jussieu’s campus in Paris’s Left Bank reshuffled its labs’ locations five times due to ongoing asbestos removal, giving the faculty no control and little warning of where they would end up. An MIT professor named Christian Catalini later catalogued the 55,000 scientific papers they published during this time and mapped the authors’ locations across more than a hundred labs. Instead of having their life’s work disrupted, Jussieu’s researchers were three to five times more likely to collaborate with their new odd-couple neighbors than their old colleagues, did so nearly four to six times more often, and produced better work because of it (as measured by citations).

The lesson? We still have no idea how to pursue what former U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld famously described as “unknown unknowns.” Even an institution like Paris Jussieu, which presumably places a premium on collaboration across disciplines, couldn’t do better than scattering its labs at random. It’s not enough to ask where good ideas come from – we need to rethink how we go about finding them.

I believe there’s a third way between the diminishing returns of typical organizations and sheer luck. In Silicon Valley, they call it “engineering serendipity,” and if that strikes you as an oxymoron (which it is), perhaps we need to step back and redefine what serendipity means:

1. Serendipity isn’t magic. It isn’t happy accidents. It’s a state of mind and a property of social networks – which means it can be measured, analyzed, and engineered.

2. It’s a bountiful source of good ideas. Study after study has shown how chance collaborations often trump top-down organizations when it comes to research and innovation. The challenge is first recognizing the circumstances of these encounters, then replicating and enhancing them.

Any society that values novelty and new ideas (like our innovation-obsessed one) will invariably trend toward greater serendipity over time. The push toward greater diversity, better public spaces, and an expanded public sphere all increase the potential for fortuitous discoveries.

The flip side is that institutions failing to embrace serendipity will ossify and die. This is especially true in our current era of incessant disruption, as seen in rising corporate mortality rates and a surge of unpredictable “black swan” events. (Nassim Taleb’s advice for taming black swans, by the way? “Maximize the serendipity around you.”)

Finally, the greatest opportunities for engineering serendipity lie in software, which means we must take great care as to who can find us and how, before Google (or the NSA) makes these choices for us.

November 02, 2014 | permalink

(Originally published on November 2, 2014 at Quartz. Written with Anthony Townsend.)

The self-driving car has traveled a long and lonely road to get here. Introduced to the American public by General Motors at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, the Depression-era dream of automated highways has perpetually lagged behind the present in drivers’ rear-view mirrors. But thanks largely to Google, the future once again appears to be gaining on us. A panel of Silicon Valley technology leaders recently polled by The Atlantic expects the first fully autonomous models to roll into our driveways in 2022.

But don’t count on it. The autonomous car will not be nearly as autonomous as its champions would have you believe.

When Google’s car took its first official driving test in Nevada in 2012, it struggled at times to pass–and this was on a course and under conditions of the company’s choosing. According to the state examiner’s log published last month by IEEE Spectrum, the self-driving Toyota Prius needed human help making turns and surrendered control completely when faced with the ambiguous terrain of roadside construction. The car wasn’t tested at all at railroad crossings or roundabouts, and Nevada’s DMV had agreed beforehand not to drive it in snow, ice or fog–none of which the car was designed to operate in.

Of course, self-driving cars will get smarter as computing power increases. But they will quickly encounter another real-world complication: other breeds of self-driving cars. In September, California joined Nevada in granting autonomous licenses, and within hours Audi and Mercedes-Benz squeezed ahead of Google in securing permits. There were merely the first in line. General Motors’ Cadillac division announced in August it would offer limited autonomy by 2017, and Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk recently unveiled the Model D, an electric sedan with its own semi-autonomous features.

Further complicating matters will be unpredictable human drivers, who won’t give up their cars en masse. A survey of 1,533 US, UK, and Australian drivers published by University of Michigan researchers in July found that a majority of respondents had serious concerns about riding in autonomous cars–and more to the point, they wouldn’t pay extra for them. It’s taken more than a decade for drivers to seriously consider switching to hybrid and electric vehicles; it will take decades more to achieve a majority of self-driving vehicles on the roads.

As a result, by the time Google’s cars are ready for sale, they will have to share the roads with a slew of models produced by dozens of automakers, each with its own scheme for avoiding collisions. With traditional rules of the road shoved aside by overly cautious computers, one result might be epic gridlock, as they slow to a crawl attempting to work it out. Meanwhile, all the focus on vehicular autonomy has overshadowed the slow progress on essential protocols for car-to-car communications, an essential technology for mass automation of our roads. Drivers can expect years of technical and legal wrangling in addition to incompatibilities and glitches as Google’s and Tesla’s cars try to talk while traveling 60 miles (96 km) per hour. Tough security problems abound and various proposals to shuffle the unique ID of your car–so that it doesn’t become a privacy-compromised tracking device like your phone–have yet to be worked out.

November 02, 2014 | permalink

(Originally published in the November 2014 issue of Inc.)

Randy Petersen founded FlyerTalk, the Web’s largest frequent-flier community, in 1995 and sold it in 2007. He now runs MilePoint and BoardingArea—two more sites focusing on the ins and outs of air travel. His advice comes from hard experience, so hear him out. As told to Greg Lindsay.

Go monochrome. My uniform hasn’t changed in 20 years; every time I fly, I’m in Nike, and I’m all in black. I’m the most comfortable passenger the airline industry ever invented. I never worry about someone spilling stuff all over me. And I never have to take off a belt.

Don’t carry receipts. The worst thing is to be slowed down by paperwork. I use an app called Expensify to take a picture of every receipt as soon as it lands on the table. After that, I don’t care if I lose it.

Movies are for kids. Real road warriors get on the plane and just go to sleep. Don’t stay up all night watching movies, or waiting for someone to get upset about a Knee Defender. I’m a big believer in Benadryl. A little dose and I’m drowsy. The next thing I know, I’m where I should be.

Treat yourself. I’ve learned that in your middle years as a traveler, you stop thinking you’re invincible. It’s OK to spoil yourself along the way. Every time I see one of those half-hour massages at the airport—here’s my money, get me going. If I can’t get in a lounge for free, I’m good with spending $50. A familiar environment where I’m not fighting for power outlets is worth it. Cokes cost eight bucks in the terminal, anyway.

Stop schlepping. I still check bags, at least internationally, because you’re traveling with more than a backpack. I don’t like carrying stuff around if I don’t have to. Frequent fliers like me don’t pay $25 per bag anyway, so I might as well take advantage of it. I want to ensure I’m getting the most out of my benefits.

Arrive hungry. On board, food just doesn’t interest me. I’ve never seen it executed well on a long-haul flight, anyway.

October 24, 2014 | permalink

(This essay was commissioned by New York University’s Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management as part of its 2014 research initiative “Re-Programming Mobility: The Digital Transformation of Transportation in the United States.” It is republished here in full.)

Prologue

Las Vegas, 2016: It’s another sunny 103º day in Henderson – and the first of mandatory “dry-outs” without water service after five years of drought. Instead of driving his SUV to work – these days, it’s really just for weekend excursions – the lawyer opens the Shift app on his phone and enters his destination: Zappos’ headquarters. Seven minutes later, a chauffeured Tesla S sedan is ferrying him to work downtown, which has boomeranged from one of the poorest neighborhoods in Nevada to one of the wealthiest, thanks to Tony Hsieh.

Zappos’ CEO invested his $350 million personal fortune in creating an entrepreneurial utopia, perhaps the most ambitious piece of which was Shift – an all-inclusive car-, ride-, and bike-sharing service combining aspects of Zipcar, Uber, CitiBike, and RideScout. Instead of checking traffic or wondering when the bus will arrive, members ask the app for the fastest modes between A and B. The attorney didn’t choose a Tesla today; Shift’s “decision engine” chose for him. And while this trip is a simple pick-up and drop-off, there have been times when he’s been ordered by the app to park his Smart car in a designated spot along the curb and finish his journey on a Social Bicycle (SoBi) chained next to it – locking and unlocking both with his phone. Five hundred dollars per month is a small price to pay for mobility-as-a-service, and he knows it, because the payments on his other car had come to $750 a month before he sold it…

Milton Keynes, 2017: “The pods are naff,” the consultant’s husband had huffed when she mentioned at breakfast she had reserved one for her visit to Milton Keynes that morning. Upon arrival on the train from London, she had to admit he was right. Seeing them lined up empty outside the station, strobing in different shades of neon – looking down at her phone, she saw it was flashing the same garish shade of purple as the third one from the front – makes her reconsider her earlier enthusiasm. Approaching the two-wheeled self-driving pod resembling something out of Minority Report (a film that’s now fifteen years old, she remembers), she opens it with a tap of her phone. After placing her bag in the second seat, the door silently swings shut and then glides smoothly not onto the street, where traffic is zooming by at 70 mph, but onto the Redway pedestrian path – and without her steering.

On her way to the headquarters of Transport Systems Catapult – really, she could have walked, had she felt like traversing parking lots and dodging cars on Grafton Gate – the pod quietly creeps along the path, until it doesn’t. Whenever pedestrians, dogs, and other pods draw too close, it alternately slows, stops, or accelerates, depending on whatever algorithmic rules it silently consults. The ride lasts no more than a few minutes and is pleasantly uneventful, but by the end she’s resolved to use the city’s “mobility map” to hail one of its electric taxis after her meeting – after all, Milton Keynes had been designed for cars….

October 08, 2014 | permalink

(In June, I was asked to speak at “The Purpose City,” an all-day event hosted by the architecture firm NBBJ. The essay below is adapted from my talk.)

How should we think about the city? Metaphors are dangerous; choose the wrong one, and you’ll wreck them for a century. Le Corbusier thought of the city mechanistically, as a “machine for living,” producing the Ville Radieuse and destruction in its wake. Earlier, Patrick Geddes had thought of the city ecologically, with architects and planners playing the role of gardeners – we should prune them, not tear them out by the roots. Although evocative, neither metaphor was correct.

Perhaps a better one is a star – a metaphor proposed, appropriately enough, by the Santa Fe Institute physicist Luis Bettancourt, who describes cities as “social reactors.” Instead of combining hydrogen atoms under tremendous pressure to produce light and heat via fusion, they compress people in space and time. The fusion of social networks produces new relationships through which new ideas might flow, leading to what Jane Jacobs called “new work” in The Economy of Cities, written before mainstream economists had any language to describe how and why cities exist at all. And the more densely we can compress these networks, the faster and hotter the reaction.

Surprisingly, some of the places that do this best are “informal” ones, where people live and work off the books. We see it today in the slums of Dharavi, in Mumbai, and Lagos’ Kibera. And we saw it in post-war Tokyo or parts of New York City a century ago. All of these are or were places in which everything is an asset to be sold, traded, or rented; every street is more than just a road, but also market, and everyone is an entrepreneur by necessity. When we talk about the “sharing economy” – or the Purpose City – what we are really talking about is a slum economy.

The Mumbai-based architecture collective CRIT investigated what makes these places white-hot social reactors – and what they found was a much more intensive use of public place, especially the street. Peoples’ willingness to utilize every space for any activity – and to ignore the boundaries between the public-and-private and legal-and-illegal – created the conditions in which fusion can occur.

From this research, CRIT identified two characteristics that make these districts special. The first is “the blur,” the compression of living, working, moving, and making into the same place and time. The second is the city’s “transactional capacity,” which doesn’t just mean market transactions, but personal ones – the ability to meet and converse. Slums, of course, are terrifically (and horrifically) transactional, where simply using the toiler carries a price. But they’re places of astonishing productivity as well.

A few oft-cited statistics estimate Dharavi has an economic output of nearly $1 billion each year, and that 85% of India’s jobs are in informal, unincorporated enterprises with fewer than ten employees. Seen one way, Dharavi is a hopeless slum; seen another, it’s the Lower East Side of New York a century ago.

No one wants to live in a slum, of course. But what can we learn from them in order to maximize the blur, and in turn maximize the output of a city’s social reactor? At one extreme is Le Corbusier’s radiant city of high-rises – modernist masterpieces with no blur. At the other is the slum, which lacks even the most basic services and as a result is constantly in motion. Where is the sweet spot between the two? Our goal should be to avoid over-formalizing the city, to create more interstitial spaces where human fusion can happen.

This is hardly a new idea. Jacobs reached the same conclusion when she wrote “new ideas must use old buildings.” Jurgen Habermas traced the beginning of such spaces to the London coffeehouses of the 17th century, his archetypal example of the public sphere. That was the London of Samuel Pepys – the original mobile worker. He worked from home and his office next door, from court and the docks, and from the taverns and coffe houses in an astoundingly blurry city. (Pepys greatest lament – all the time he wasted waiting for no-shows – has at last been solved by texting.)

The challenge facing us is how to build these blurry spaces, especially in a time of austerity, where resources are not forthcoming. We will have to hack the cities we have. For example, Marcus Westbury is an Australian arts festival organizer who decided to help his hometown of Newcastle bring its boarded-up downtown back to life again. What he discovered is that downtown’s landlords were perfectly happy to leave it that way – they couldn’t be bothered to lease their empty storefronts to entrepreneurs or artists because tax laws and leases favored keeping them empty until someone with deeper pockets came along. Westbury’s solution at Renew Newcastle was to deploy a new system of short-term, lightweight permits, hacking the existing regulations to put hundreds of people into spaces, thus increasing the blur downtown. Organizations in other cities are doing something similar, whether it’s New York’s Made in Lower East Side, or London’s 3space, which won the most recent FT/Citi Ingenuity Award.

Through initiatives such as these, combined with the startups of the sharing economy, we’ve taken the dynamics of slums and recreated them using digital networks. This is what post-austerity America looks like – with Airbnb, every home is an unlicensed hotel, and with UberX and Lyft, everyone with a car is a cab driver. And with new apps like Breather, your apartment becomes someone’s office for an hour.

If cities are comprised of social networks moving through space in time, with nodes overlapping and fusing, then those nodes are becoming increasingly visible. Tinder is a crude but telling example. The reason Tinder is the fastest-growing dating app in the history of online dating is because it’s proximity-based – the promise is that if you make a match, they’re close at hand. If serendipity has traditionally been the spark igniting fusion, then an entire generation of apps is trying to engineer it. As we overlay more information, and more legibility on top of cities, we make the blur visible – and actionable. And manipulable.

The real test will be to implement these tools and networks in a place like Detroit, which has tens of thousands of abandoned, but still salvageable buildings, all of which have nominal owners, many of which are in foreclosure, but all of which exist as a purely physical fact – which means they can be occupied, activated, and used to restore the city’s blur. We’ll need new networks that enhances our ability to use these spaces by making them visible and usable – and does so as a public good, not a profit center.

So when it comes to building the Purpose City, what we’re really trying to do is accelerate the speed of its reactions. We’re trying to build new spaces for encouraging serendipity and forging new relationships. We’re trying to create public spaces that increase the density of interaction rather than just people. When we do that, we create a brilliant city as well.

September 23, 2014 | permalink

While at Techonomy Detroit last week, I also moderated a session on the future of transportation starring Ford’s Don Butler, Alta’s Jeff Olson, Urban Engines’ Shiva Shivakumar, and Streetline’s Zia Yusuf. What does Detroit look like in a world of seamless mobility? Click on the video above to find out.

September 19, 2014 | permalink

At the Techonomy Detroit conference: From left, Phil Cooley of Ponyride in Detroit, Gabriella Gomez-Mont of City Laboratory in Mexico City and Greg Lindsay of World Policy Institute and Fast Company lead a panel discussion on how technology will shape the future of cities. (Elizabeth Conley / The Detroit News)

September 19, 2014 | permalink

(A shorter version of this story originally appeared at Harvard Business Review on September 18, 2014.)

To hear Samuel Pepys tell it, the 17th Century diarist and Royal Navy clerk was the world’s first mobile worker. As the architect Frank Duffy notes in his book Work and the City, Pepys tirelessly traversed London giving and taking orders and trading gossip, whether at the docks, at court, or in one of city’s fashionable new coffee houses. His greatest annoyance? Having “lost my labour” when one lord or another failed to appear for a meeting.

Some things never change, but Pepys’ peripatetic routine underscores just how recent, and how artificial, the modern office is. The notion that a single organization would monopolize a space, often for a single function, is a distinctly 20th century one. The demands of the vertically integrated corporation required tight coordination in both space and time, what Duffy calls “synchrony” and “co-location.” The solution was the skyscraper, and later the suburban campus.

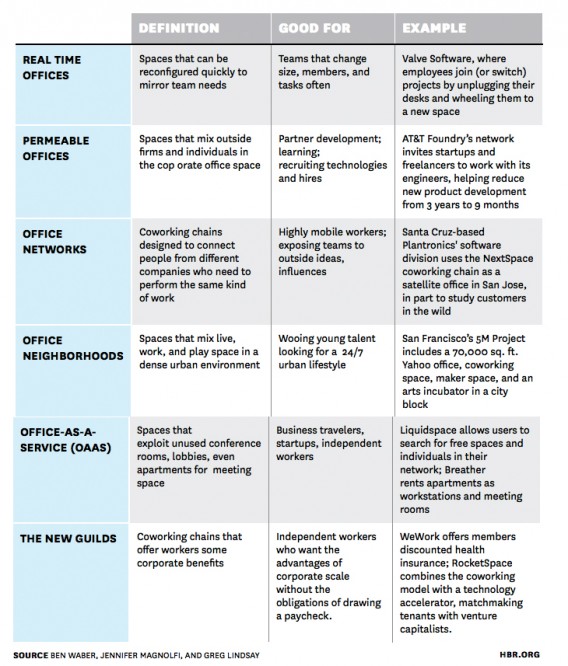

But as workflows and processes moved first into software and then into the cloud, the questions of how and where and with whom we should work are being asked anew. Just as Pepys’ treated London’s coffee houses as an extension of his office, new heterogenous workspaces are emerging that capitalize on these changes. Here’s a short taxonomy:

1. Real-Time Offices

The typical office is designed to last years, leaving teams to struggle against static layouts even as the pace of change and competition accelerates. Real-time offices attempt to flip the script, dynamically reconfiguring themselves to mirror how work actually gets done, rather than forcing workers to conform to its limitations. Facebook will try to do this with the Frank Gehry-designed extension of its Silicon Valley campus – nearly half a million square feet of open space until one roof in which its engineers can rearrange desks at will . But the best example may be the billion-dollar videogame-maker Valve Software, where employees decide to join (or switch) projects by unplugging their desks and wheeling them over to their new team . As a result, very important decision – from who to hire to which games will ship – begins as a choice of who to sit with.

2. Permeable Offices

Instead of retreating into their shells, some organizations welcome other firms and freelancers to work alongside employees in hopes of learning from them. Permeable offices act as a membrane, selectively allowing these strangers inside. Capital One , Rackspace , Steelcase, and Amway have all experimented with this model, but the most successful example may be AT&T’s Foundry network of innovation centers . In those offices, selected startups and entrepreneurs work in cross-company teams with AT&T partners such as Intel, Cisco, and Ericsson along with its own engineers. One of these startups, Intucell, improved AT&T’s call retention and throughput speeds by 10% and was later bought by Cisco for $475 million . In general, Foundry teams have cut the development time of new products from 3 years to 9 months.

3. Office Networks

Behind the current backlash against the open office and its constant interruptions is the dawning recognition that not one workspace fits all. According to Gensler’s 2013 U.S. Workplace Survey , knowledge workers with choices of when and where to work are significantly more satisfied, effective, and innovative than their peers. Taking advantage of this trend, coworking chains such as Work in Progress and NextSpace have begun offering memberships across a range of location, with each possessing its own vibe, design, and clientele. The Santa Cruz-based headset-maker Plantronics uses NextSpace’s Bay Area branches as its satellite offices, with the company’s software division electing to work from San Jose to be closer to new hires and customers .

4. Office Neighborhoods

Realizing the benefits of urban amenities when it comes to wooing talent, some companies and developers are treating entire neighborhoods as an urban campus. This includes Zappos and the Downtown Project’s goal of building a creative class company town from scratch, but also Seattle’s South Lake Union – where Amazon is building its permeable new headquarters – and Forest City’s 5M Project in San Francisco. The latter couples a Yahoo office with a coworking space, maker space, and arts incubator in a single city block – a major selling point to tenants for the 2 million sq. ft. of office space it intends to build on the site.

5. Office-as-a-Service (OaaS)

The consulting and design firm Strategy Plus estimates workspace utilization peaks at 42% during the workday, meaning more than half of all (technically occupied) offices are currently sitting empty. They comprise a ripe opportunity for the so-called “sharing economy” to transform every underutilized conference room, hotel lobby, or even home into a bookable meeting space or quiet nook. AirBnB would appears to be a natural fit for this role, but the company seems content with overnight stays. Enter more aggressive startups such Liquidspace , which not only allows users to search for usable spaces on its network, but also specific individuals – who would you like to work with today?

6. The New Guilds

Company men not only looked to GE, GM, and IBM for a paycheck and benefits, but also for an identity, too. The same can’t be said of an estimated 53 million American freelance workers , many of whom have had those identities – and their benefits – stripped from them during the long recession. Enter a handful of coworking chains and startup incubators to fill the void for those affluent enough to pay for the advantages of corporate scale without the obligations of drawing a paycheck. WeWork offers its 3,500 members discounted health insurance, hosts an annual raucous summer camp , and touts itself as “the physical social network.” San Francisco’s RocketSpace combines coworking with a tech accelerator, matchmaking tenants with hungry venture capitalists who consider their residency a badge of prestige.

September 12, 2014 | permalink

Fast Company’s Lydia Dishman offers her take on my story in the new issue of Harvard Business Review (written with Ben Waber and Jennifer Magnolfi).

Forget what you know about how to maximize productivity.

That includes knowing which tasks can be breezed through with the help of a playlist, or exactly when to down that cup of coffee (or switch to another beverage) and when to mindlessly surf the web.

According to a new report published in Harvard Business Review, the key to unlock the greatest productivity isn’t necessarily in the hands of the individual employee. Rather, authors Ben Waber, Jennifer Magnolfi, and Greg Lindsay posit that chance and face-to-face encounters are the way anyone working in the knowledge economy is going to improve performance. That’s in spite of technology that keeps us “connected,” even when we work remotely.

Dishman was kind enough to quote me opining on the invisible social networks within organization and how the combination of data and workspace design can reveal and enhance them:

“One thing I’m finding is the notion there are a lot of informal social networks inside of organizations,” says Lindsay. From chat rooms like Yammer and Slack to actual gatherings in a break room, these communication networks have the potential to reveal a lot more about the employees than an org chart.

He cites the work of Ronald Burt at the University of Chicago, who discusses “structural holes” in organizations. By studying informal communication, Burt’s been able to show how people who straddle different groups are actually more powerful than their titles would suggest. “How many years before they redesign [the organizational hierarchy],” he muses.

» Folllow me on Twitter.

» Email me.

» See upcoming events.

Greg Lindsay is a generalist, urbanist, futurist, and speaker. He is a non-resident senior fellow of the Arizona State University Threatcasting Lab, a non-resident senior fellow of MIT’s Future Urban Collectives Lab, and a non-resident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Strategy Initiative. He was the founding chief communications officer of Climate Alpha and remains a senior advisor. Previously, he was an urban tech fellow at Cornell Tech’s Jacobs Institute, where he explored the implications of AI and augmented reality at urban scale.

----- | January 22, 2024

The Future of Generative AI in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction

----- | January 1, 2024

----- | August 3, 2023

CityLab | June 12, 2023

Augmented Reality Is Coming for Cities

CityLab | April 25, 2023

The Line Is Blurring Between Remote Workers and Tourists

CityLab | December 7, 2021

The Dark Side of 15-Minute Grocery Delivery

Fast Company | June 2021

Why the Great Lakes need to be the center of our climate strategy

Fast Company | March 2020

How to design a smart city that’s built on empowerment–not corporate surveillance

URBAN-X | December 2019

CityLab | December 10, 2018

The State of Play: Connected Mobility in San Francisco, Boston, and Detroit

Harvard Business Review | September 24, 2018

Why Companies Are Creating Their Own Coworking Spaces

CityLab | July 2018

The State of Play: Connected Mobility + U.S. Cities

Medium | May 1, 2017

Fast Company | January 19, 2017

The Collaboration Software That’s Rejuvenating The Young Global Leaders Of Davos

The Guardian | January 13, 2017

What If Uber Kills Public Transport Instead of Cars

Backchannel | January 4, 2017

The Office of the Future Is… an Office

New Cities Foundation | October 2016

Now Arriving: A Connected Mobility Roadmap for Public Transport

Inc. | October 2016

Why Every Business Should Start in a Co-Working Space

Popular Mechanics | May 11, 2016

Can the World’s Worst Traffic Problem Be Solved?

The New Republic | January/February 2016

January 31, 2024

Unfrozen: Domo Arigatou, “Mike 2.0”

January 22, 2024

The Future of Generative AI in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction

January 18, 2024

The Promise and Perils of the Augmented City

January 13, 2024