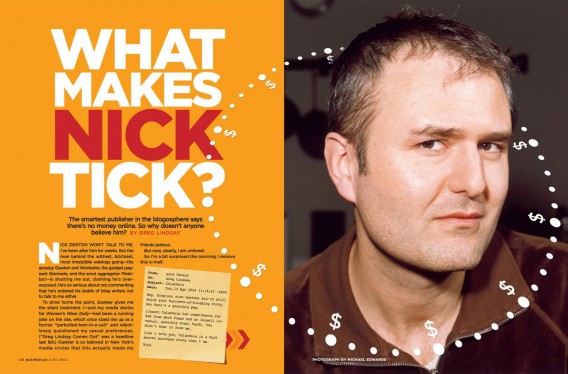

Nick Denton won’t talk to me. I’ve been after him for weeks. But the man behind the wittiest, bitchiest, most irresistible weblogs going—the gossipy Gawker and Wonkette, the gadget pageant Gizmodo, and the smut aggregator Fleshbot—is shutting me out, claiming he’s overexposed. He’s so serious about not commenting that he’s ordered his stable of blog writers not to talk to me either.

To drive home the point, Gawker gives me the silent treatment. I—and my media stories for Women’s Wear Daily—had been a running joke on the site, which once sized me up as a former “parboiled-ham-in-a-suit” and relentlessly questioned my sexual preferences. (“Greg Lindsay Comes Out” was a headline last fall.) Gawker is so beloved in New York’s media circles that this actually made my friends jealous.

But now, clearly, I am unloved.

So I’m a bit surprised the morning I receive this e-mail:

From: Nick Denton

To: Greg Lindsay

Subject: Calacanis

Date: Tue,13 Apr 2004 11:16:27 -0400Hey, Greg—not sure whether you’re still doing your business-of-blogging story. But here’s a possible peg.

[Jason] Calacanis has commitments for $4M from Mark Cuban and an Israeli investor, possibly Yossi Vardi. You didn’t hear it from me.

Like I told you, Calacanis is a much better business story than I am.

Nick

Could Denton be capitulating? Maybe his Calacanis gambit was a bid to pique my interest. Jason Calacanis, as you may know, was biggish during the bubble years as, among other things, the publisher of the now-defunct Silicon Alley Reporter in New York City. He’s the closest thing Denton has to a competitor these days. But as a blog impresario, he’s not a business story.

Denton, on the other hand, may be quietly figuring out the most vexing problem of new media—how to make it pay. That’s the more provocative scenario, anyway. Less interesting is the possibility that he’s simply manipulating me to write about him. After all, he’s an expert at getting the right kind of buzz, which helps inflate his properties’ value. And that could be the real endgame: finding someone to unload his business on at the right time. Sound too cynical? One of Denton’s first companies threw networking parties for dotcom naifs. And that one sold for millions at the top of the bubble.

Any way you look at it, you have to conclude that Denton is wily. Consider his blog business model. A decade ago, media companies sank untold millions of dollars into building and staffing websites. Most of them are still in the red. It turned out that most Net users don’t want to pay for content, so new-media publishers had to rely on the trickle of revenue that came from online ads.

Denton learned from that debacle and embraced weblogs, which are the LEDs of the media firmament: They require almost no resources to run. His mini media empire, Gawker Media, has no offices, no proprietary technology, and no full-time employees, yet it can attract audiences big enough to generate ad revenue. Better still, the “content” is virtually free, since it consists of little more than snarky comments pointing to other sites (mostly newspapers and magazines) that do spend money or time creating content. It’s so dumb, it works: Denton’s blog model is leaner than a George Foreman turkey burger. And it’s apparently already returning a modest profit—with the potential to deliver substantially more within a few years.

Of course, if it were that simple, everyone would be doing it. Denton, 37, has figured out a couple of tricks. By offering fame rather than fortune, he’s persuaded talented writers to work for him for less money than they’d make pulling cappuccinos at Starbucks. And he picks subjects for his blogs that are irresistible to the chattering classes—media, power, sex, and toys. In the end, it costs Denton a few thousand bucks per month for each site, in return for a monthly audience of about 1.6 million young, media-savvy readers. Several Internet user studies recently concluded that the total blogger audience is only 13 million to 14 million readers. Denton is skimming off the demographic cream—the influential chatterati.

How does he turn that cream into milk money? The revenues at his flagships, Gawker and Gizmodo, have nearly tripled since last fall, to about $6,000 a month each. Both are in the black, several Denton associates claim. Based on current rates and inventory, a quick calculation suggests Denton may be grossing about $250,000 a year.

Given the rate of growth, he could be taking in $1 million annually by next year—and that’s assuming he doesn’t add more sites. Naturally, he does plan to add more: Defamer, an L.A. version of Gawker, debuted in May with a buzz-provoking anonymous byline, and Denton is considering launching a travel blog.

“My guess is that Nick has been downplaying the size of the opportunity of blogging,” says Fred Wilson, a venture capitalist and blogger himself, “because he’s not excited about the prospect of lots of capital coming in and creating competition for him.”

It sounds ambitious for a man who has consistently talked down his own financial ambitions. So what really makes Nick tick?

Denton came from nowhere, although he wasn’t a nobody. Half-English and half-Hungarian, he was Oxford-educated and lucky to be in Budapest when the Berlin Wall fell. He covered the end of communist Romania for a London newspaper and parlayed that into a gig at the Financial Times through the ‘90s, eventually covering Silicon Valley. Then he caught the bug, having perversely decided that journalists were expendable. He launched a company called Moreover, whose goal was to aggregate on one site all the world’s news, disintermediating most of his former profession. (This is a theme; when I first met Denton before working on this piece, he promised that Gawker would commoditize my then-job of media reporter.)

Back in London, he began hosting dotcommer parties that grew so big, he and his three partners decided there must be a revenue stream in them somewhere. After throwing half a dozen events, Denton bounced between London, San Francisco, and New York, raising money for Moreover. His partners carried on with what became First Tuesday—a face-to-face network that connected entrepreneurs with investors over drinks—which they sold at the peak of the bubble, in July 2000, to the Israeli firm Yazam. Though no one involved will say how much, if anything, Denton made from the deal, the four partners and their investors got a reported $50 million in cash and stock in the combined company. Six months later, Yazam sold First Tuesday for a pittance and shortly thereafter sold itself to a company that ran manufacturing facilities in prisons using inmate labor. It was a valuable lesson.

“Nick understands the difference between valuation and value,” says one of First Tuesday’s co-founders, former Wired UK editor John Browning. “He’s perfectly able to say, ‘This is undervalued and worth investment,’ and he’s equally willing to say that the market is valuing this business at more than its underlying worth.” Denton’s modus operandi is to buy the former and sell the latter.

While negotiating First Tuesday’s sale, he was simultaneously trying to raise a decisive round for Moreover. He succeeded, finding $21 million, but stepped down as CEO in August 2001 in favor of someone with more salesmanship. He then left for London to care for his ailing mother. Moreover still slogs toward profitability today, having become little more than a search tool for publicists.

Well before he left, Denton had plans for a new kind of site: a blog built around gossip. In early 2001 he even asked Valley gossip queen Chris Nolan if she’d run it. She declined, and now recalls, “He knew then what his business model would be. He knew how much he wanted to pay. He wanted one person to blog gossip. He wanted to pay [the writer] $1,000 a month, with a set number of entries a day.”

As a sort of shakedown cruise, in August 2002 he launched his first blog, Gizmodo. Denton hired Pete Rojas, a gadget specialist he had met in the Moreover days, and started applying some of the techniques that he would later perfect. His insight from having read so many blogs during his downtime after Moreover was that blogging’s laws of popularity revolved around the frequency of posts, not the density. Readers wanted ever-quicker hits, not chewiness. Of course, tone and attitude were also key.

Elizabeth Spiers, a former securities analyst he had met at a party of bloggers in early 2002, had exactly the right bite for his gossip site. He liked her scathing prose, and hired her as editor at $1,000 a month. They launched Gawker in December 2002.

It scored instant points with Manhattan media types by sniping at the biggest targets, everyone from Donald Trump to former New Yorker editor Tina Brown. But Spiers’s breakthrough came within a month of Gawker’s launch, when she published “The Quest for the Perfect Coke Dealer.” The piece was a taped interview with an anonymous “Ivy-educated Wall Streeter in her late 20s” who railed about customer service in the narcotics business. Spiers quickly became the “it” girl, prompting showers of party and dinner invitations from the very people she mocked.

By last summer their relationship was becoming strained, her friends said. The two bickered incessantly—symptoms of a professional marriage heading for divorce. So when New York magazine gave Spiers a weeklong audition for a staff job in September, Denton replaced her.

He quickly launched two more blogs. First was Fleshbot, making Denton a pornographer-by-proxy with its hard-core links. Having timed Fleshbot’s debut for the day the Paris Hilton tape went wide on the Web, Denton earned another plug in the New York Times.

Wonkette followed in January, filling a niche that was genuinely underserved: scorched-earth gossip from inside the Beltway. Its editor, old new-media hand Ana Marie Cox (once the editor of the now-closed Suck.com), predictably roiled the locals, leading to the obligatory Times piece. This time the paper tut-tutted the site’s willingness to run just about anything, even rumors that reputable journalists had already passed on. Denton’s response to the paper and potential litigation: Bring it on.

The Gawker Media sites continued to race ahead. The only speed bump occurred at Gizmodo, where Rojas grew sick of working for the Man. It was Spiers all over again, with a twist: When Denton refused to give Rojas a piece of the action, the editor quit on a Friday and started a competing blog, Engadget, the following Monday. His 50-50 partner: Jason Calacanis.

Calacanis is late to the blogging game, or at least later than he was to the rise and subsequent overinflation of New York’s Silicon Alley. His strategy appears to be to exploit Denton’s weakness. Rather than paying bloggers a pittance, he’s partnering with them, letting them keep their sites and half the revenue generated by ads. His company is the Weblogs Inc. Network. Get it? WIN.

While Denton courts the media, Calacanis is busy trying to hijack the business-to-business newsletter trade with a convoy of vertically focused blogs covering business, science, entertainment, and tech. He wants to make his fortune through volume, by selling low-cost ads and sponsorships across what he hopes will be several hundred sites. He’ll also sell his own company’s blogging software (called Blogsmith) and use his blogs as rallying points to sell conferences and research. This was essentially the model behind Silicon Alley Reporter, which morphed several times after the bust before it was sold last year to Wicks Business Information, now a part of Dow Jones.

Perhaps Calacanis had the answer to the riddle of the Denton. As luck would have it, I ran into him at the semiannual blogger confab BloggerCon at Harvard this spring. I asked him about Mark Cuban and Nick’s e-mail.

Calacanis smirked. “I don’t ever answer that question,” he said. “Why would I want people to know I have money? Why would I want to legitimize the space?” Clearly, he and Denton were playing a game of chicken, each desperate to avoid the stigma of having touched off more hype and encouraged speculators to enter the nascent market. Yet, while Calacanis wouldn’t discuss his own plans, he was happy to assay Denton’s. “He’s going to keep the cash burn low, build a brand, and then flip it,” Calacanis claimed. And he wished Denton luck. “Whoever he sells Gizmodo to, two years from now, sets the bidding for Engadget, and whoever loses will buy Engadget for a higher price.” Two weeks later Calacanis suggested that Weblogs Inc. might one day be worth $30 million.

One thing that appears to be part of Denton’s game plan—and perhaps simply a faulty part—is Kinja, a blog-search site that debuted to great fanfare in April. Kinja had been Denton’s top-secret project for more than a year. Built by Meg Hourihan—who co-invented the breakout-hit self-publishing program Blogger and thus blogging itself as a mass medium—Kinja was originally conceived as a tool for marketers. It was to be an algorithmic divining rod that would scour blog links for trends. How much would Nike or Burger King or Sony pay to watch the tipping point happen in real time?

After only a few months in the lab, the Kinja team scrapped the marketing-tool angle. The project persisted as a kind of Google for blogs, and at launch, to no one’s surprise, the New York Times ran a piece about it. But so far, the thing has turned out to be an overhyped bust on par with “push technology.” Hourihan quit the day of its launch. Power bloggers eschew it as a weaker version of the programs they already use, the blog-gathering RSS applications, which keep tabs on hundreds of blogs at once. People new to the blogging world, of course, don’t look at it at all.

Not long after I receive my first e-mail from Denton, he sends another. “OK, you win,” he writes. But he has ground rules. I can’t use his words to further what he perceives as my agenda—i.e., whipping up a frenzy of big-money interest in what he has come to consider his sandbox. Not a problem, I say. Then he sets the terms of the exchange: e-mailed questions only, with final answers subject to approval. We continue to haggle, and finally he agrees to a telephone interview.

Denton begins by bemoaning my interest in his story. “I’m nostalgic for the recession,” he says. “There was no excitement, no interest on the part of venture capitalists or journalists. You could just plug away without the distraction of inflated expectations—or greed.”

But that’s over, I tell him. The excitement’s back; tech’s back. People do care. During lunch at BloggerCon, someone pointed out that it felt like InternetWorld ‘94 all over again—that blogging, while big, was about to get huge. The bloggers seemed to want it that way. They packed the room for a session on blogging as a business and decided that what they really needed was a blogging trade association. They were practically ready to form a union.

“People are starting to get excited—overexcited—about the revenue potential,” Denton concedes. But then he objects: “Who the hell knows how big blogs are going to be in 10 years? Right now, they are small businesses, but they get all this attention because the media is obsessed by media. A blog empire? That’s a joke. I’m not looking for outside money. Which is why I don’t have to hype the potential.”

I ask Denton what will happen to the next editor who decides he or she wants a piece. He explains that since he has no plans to take his company public, he won’t offer equity positions. “I’m a traditionalist: I believe that writing is a job and writers should get paychecks. It would be entirely bogus to offer people empty revenue-share promises or meaningless equity.”

So what’s he really after?

That’s easy, Denton says: Freedom. Freedom of the press. Freedom of speech. Freedom from the rules that bind our profession.

He insists that what’s in it for him is the thrill of having invented a media business that doesn’t behave like other media. His sites are breaking fizzy, glamorous scoops, spreading dirt, and reaping the buzz. He’s running a tabloid out of his house—and loving it. “We don’t have to kowtow to investors,” he says. “We don’t have to suck up to advertising. And it means almost complete editorial freedom—which shows in the exuberance of the sites.”

He starts to sway me. Media today is repressed and apologetic and not at all the woolly way to make a living it once was. It’s hardly fun anymore. Gawker Media is media acting out, unencumbered by the pressures of advertising or ethics. I get that, and it moves me.

But later, after talking to him, I run the numbers again. If he were simply looking for truly free speech, why would he need half a dozen sites? Why would he keep trying to grow Gawker Media? Why would he be so carefully trying to work me? I think back to Browning’s comments. For now, running a blog business is a blast for Denton; Gawker gets him into parties where he rubs shoulders with New York’s media elite. But once the thrill of invention is gone? After the crowds rush the door? Denton’s got an uncanny knack for knowing when a scene is over—and for finding someone willing to pay face value for his entrance ticket.

» Folllow me on Twitter.

» Email me.

» See upcoming events.

Greg Lindsay is a generalist, urbanist, futurist, and speaker. He is a non-resident senior fellow of the Arizona State University Threatcasting Lab, a non-resident senior fellow of MIT’s Future Urban Collectives Lab, and a non-resident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Strategy Initiative. He was the founding chief communications officer of Climate Alpha and remains a senior advisor. Previously, he was an urban tech fellow at Cornell Tech’s Jacobs Institute, where he explored the implications of AI and augmented reality at urban scale.

----- | January 22, 2024

The Future of Generative AI in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction

----- | January 1, 2024

----- | August 3, 2023

CityLab | June 12, 2023

Augmented Reality Is Coming for Cities

CityLab | April 25, 2023

The Line Is Blurring Between Remote Workers and Tourists

CityLab | December 7, 2021

The Dark Side of 15-Minute Grocery Delivery

Fast Company | June 2021

Why the Great Lakes need to be the center of our climate strategy

Fast Company | March 2020

How to design a smart city that’s built on empowerment–not corporate surveillance

URBAN-X | December 2019

CityLab | December 10, 2018

The State of Play: Connected Mobility in San Francisco, Boston, and Detroit

Harvard Business Review | September 24, 2018

Why Companies Are Creating Their Own Coworking Spaces

CityLab | July 2018

The State of Play: Connected Mobility + U.S. Cities

Medium | May 1, 2017

Fast Company | January 19, 2017

The Collaboration Software That’s Rejuvenating The Young Global Leaders Of Davos

The Guardian | January 13, 2017

What If Uber Kills Public Transport Instead of Cars

Backchannel | January 4, 2017

The Office of the Future Is… an Office

New Cities Foundation | October 2016

Now Arriving: A Connected Mobility Roadmap for Public Transport

Inc. | October 2016

Why Every Business Should Start in a Co-Working Space

Popular Mechanics | May 11, 2016

Can the World’s Worst Traffic Problem Be Solved?

The New Republic | January/February 2016

January 31, 2024

Unfrozen: Domo Arigatou, “Mike 2.0”

January 22, 2024

The Future of Generative AI in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction

January 18, 2024

The Promise and Perils of the Augmented City

January 13, 2024