(Global Solution Networks, a research initiative of the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto, in collaboration with The Tapscott Group – an international think tank headed by Don Tapscott – asked me to prepare a report on new approaches to urban mobility in an era of mega-urbanization, economic austerity, and climate change. The introduction to the report is below; the complete report is available for download at the GSN Website.)

Introduction

Catalyzing urban mobility in an era of mega-urbanization, economic austerity, and climate change demands new approaches to transportation planning and policy, especially in the megacities of the Global South. Tackling traffic congestion in such cities as Nairobi, Manila, Delhi, and Mexico City is essential to reducing carbon emissions while increasing the scope of inhabitants’ opportunities and quality-of-life.

Tackling traffic problems will require marshaling untapped resources and recruiting unlikely allies. Conventional transportation planning by public- and private-sector actors alike ignore the informal transportation networks ferrying millions of commuters daily, whether they’re dollar vans in New York or matatus in Nairobi. New technologies and services will play a pivotal role in discovering, integrating, and delivering more inclusive, more fluid, and less polluting transportation networks comprising existing modes, from metros and bus rapid transit (BRT) to rickshaws and unlicensed jitneys.

In this context, Global Solution Networks are emerging around what has been called the “new mobility” – a shift away from private motor vehicles toward multi-modal networks mediated by information. Some of these networks are generating and safeguarding the new data standards and protocols enabling these networks; others are introducing and lobbying for more sustainable and more equitable transportation policies around such networks; and still others are delivering services that are neither traditional public transit nor private operators, but a more resilient hybrid.

Hot, Broke, and Gridlocked

Mobility and congestion have become paramount issues for cities facing an unprecedented wave of rural-to-urban migration. More than half the world’s population – 3.5 billion people – now live in cities, and their numbers are expected to nearly double by 2050 at a rate of more than a million migrants weekly.

An enormous quantity of infrastructure is required to house, employ, and transport these new arrivals – an estimated $350 trillion worth, of which $84 trillion should be earmarked for moving people and goods. Arguably, transportation is the most important investment cities can make, given its impact on land use, labor mobility, energy consumption, and air pollution, all of which in turn have profound implications for both accessibility and sustainability.

The speed and scale of mega-urbanization – and with it, epic traffic congestion and its accompanying climate impact – has overwhelmed policymakers. They struggle to understand new patterns of informal transit, are unable to finance large investments due to austerity, and have largely been unable to reach consensus on how to integrate existing investments into a more coherent mobility system.

An example: Brazilian officials were dumbstruck last year when a $.09 increase in Sao Paulo’s transit fares triggered months of violent demonstrations. President Dilma Rousseff’s pledge to spend $22 billion on improving the nation’s transit infrastructure failed to mollify protestors and triggered a slide in the Brazilian real on fears of a widening budget deficit. Nor is money a sufficient answer – a lack of political will, a shortage of experienced project managers, and unrealistic financial expectations have prevented the construction of high-speed rail between Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo despite existing financing. That may be for the best –The New York Times reported in April that despite billions spent, Brazil is littered with unfinished infrastructure projects in the wake of hosting the FIFA World Cup.

Meanwhile, Manila’s traffic is considered so intractable that policymakers and business leaders alike have impractically called for “decongesting” (i.e., de-populating) the megacity. (A call echoed in Nairobi. ) This is impossible. Urbanization has historically been driven by the desire for economic opportunity. Cities began as nodes of exchange and trade and today they might functionally be defined by the size and scope of their labor sheds, i.e., the ability to live and work anywhere within them. For this reason, efficient transportation systems are vital to residents’ health, wealth, and well-being, whether measured in terms of productivity, income, or social mobility. Polycentric cities such as Manila feel the strain of congestion acutely, as traditional linear public transit systems (e.g., metros and BRT)are ill-suited for lower-density sprawl.

Instead, residents have turned to informal and semi-regulated transit services such as auto-rickshaws and motorcycles. Manila, for instance, is home to an estimated 3.5 million “trikes” – motorbikes with metal passenger sidecars welded to their sides. Dangerous, noisy, and dirty, such vehicles are also among the most polluting on a per passenger mile basis. This is especially significant in that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has found transport to be responsible for 23% of world energy-related greenhouse gas emissions, with about three quarters coming from road vehicles. Transport has been the fastest growing energy sector for twenty years, relying on a single fossil fuel for 95% of its energy.

With oil prices hovering around $80 per barrel despite hydraulic fracking and new fields coming online in Iraq and elsewhere, it would appear ground transportation faces persistently high (and eventually higher) fuel costs for the foreseeable future. If that weren’t enough, the IPCC’s increasingly dire warnings about climate change have reinforced the need for more sustainable forms of transportation. As events like COP 15 and Rio+20 have demonstrated, nation-states and traditional political actors have made little headway on addressing the underlying issues of climate change, leaving it to local forms of governance and non-traditional actors to adopt and implement policies for sustainable transportation.

As with other global issues such as climate change, gender-based violence, and the prevention and management of global health pandemics, the gridlock plaguing urban centers will not be solved by governments alone. Nor can it be satisfactorily addressed by individual private enterprises or non-profit organizations. Instead, the world needs bold new approaches leveraging contributions and resources from all sectors of society. In short, new global solution networks are needed to design and implement sustainable transportation solutions, transfer knowledge and best practices, and bridge the governance gap between governments, corporations, and citizen stakeholders.

As defined by the GSN program, a Global Solution Network consists of diverse stakeholders, organized to address a global problem, making use of transnational networking, with a membership and governance that are self-organized. Given the lack of leadership and funding across much of the Global South, GSNs have a significant role to play in designing, advocating for, and delivering inclusive, low-carbon transportation schemes. Aiding them are new technologies – from smart phones to electric vehicles to low-sulfur fuels – to compensate for a lack in traditional infrastructure investment.

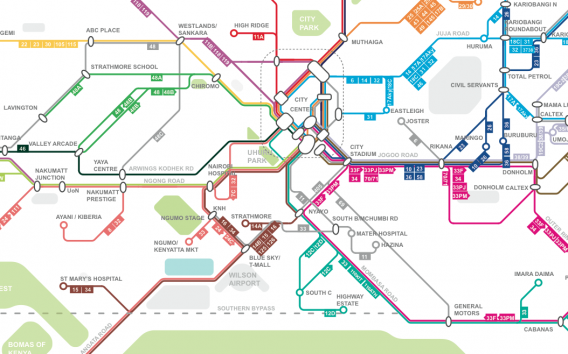

This report is an analysis of four such GSNs to illustrate how traditional approaches to transportation planning and transit are changing. Nairobi’s Digital Matatu effort mapped the city’s semi-formal bus networks, providing the information for what has become an entire generation of real-time transit apps.

G-Auto has reinvented auto-rickshaw service in five Indian cities using call centers, text messaging and apps. Drivers joining its network are held to higher performance standards in exchange for health insurance, access to credit, and educational allowances for their children. The net result is better service for passengers, a higher quality of life for drivers, and fewer empty rickshaws, which in turn reduces congestion and emissions. G-Auto is the 2014 winner of the Grand Mobi Prize recognizing innovation in sustainable transportation.

The prize, in turn, is the creation of SMART (Sustainable Mobility & Accessibility Research & Transformation), a GSN at the University of Michigan creating knowledge and building capabilities around what it calls the “new mobility ecosystem.”

The fourth example is EMBARQ, an initiative of the World Resources Institute operating five research centers around the world drafting and implementing sustainable transportation policies, including Mexico City’s BRT system and national fuel efficiency standards.

In the taxonomy of GSNs, Digital Matatu is a hybrid of a Standards and Knowledge Network; G-Auto is an Operational and Delivery Network; SMART is a Knowledge Network; and EMBARQ is a hybrid of Policy, Advocacy, and Operational and Delivery Networks. Considering each example in turn, this report will explore the ramifications of GSNs when it comes to urban mobility and congestion, concluding with lessons for network leaders.

» Folllow me on Twitter.

» Email me.

» See upcoming events.

Greg Lindsay is a generalist, urbanist, futurist, and speaker. He is a non-resident senior fellow of the Arizona State University Threatcasting Lab, a non-resident senior fellow of MIT’s Future Urban Collectives Lab, and a non-resident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Strategy Initiative. He was the founding chief communications officer of Climate Alpha and remains a senior advisor. Previously, he was an urban tech fellow at Cornell Tech’s Jacobs Institute, where he explored the implications of AI and augmented reality at urban scale.

----- | January 22, 2024

The Future of Generative AI in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction

----- | January 1, 2024

----- | August 3, 2023

CityLab | June 12, 2023

Augmented Reality Is Coming for Cities

CityLab | April 25, 2023

The Line Is Blurring Between Remote Workers and Tourists

CityLab | December 7, 2021

The Dark Side of 15-Minute Grocery Delivery

Fast Company | June 2021

Why the Great Lakes need to be the center of our climate strategy

Fast Company | March 2020

How to design a smart city that’s built on empowerment–not corporate surveillance

URBAN-X | December 2019

CityLab | December 10, 2018

The State of Play: Connected Mobility in San Francisco, Boston, and Detroit

Harvard Business Review | September 24, 2018

Why Companies Are Creating Their Own Coworking Spaces

CityLab | July 2018

The State of Play: Connected Mobility + U.S. Cities

Medium | May 1, 2017

Fast Company | January 19, 2017

The Collaboration Software That’s Rejuvenating The Young Global Leaders Of Davos

The Guardian | January 13, 2017

What If Uber Kills Public Transport Instead of Cars

Backchannel | January 4, 2017

The Office of the Future Is… an Office

New Cities Foundation | October 2016

Now Arriving: A Connected Mobility Roadmap for Public Transport

Inc. | October 2016

Why Every Business Should Start in a Co-Working Space

Popular Mechanics | May 11, 2016

Can the World’s Worst Traffic Problem Be Solved?

The New Republic | January/February 2016

January 31, 2024

Unfrozen: Domo Arigatou, “Mike 2.0”

January 22, 2024

The Future of Generative AI in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction

January 18, 2024

The Promise and Perils of the Augmented City

January 13, 2024